About Us

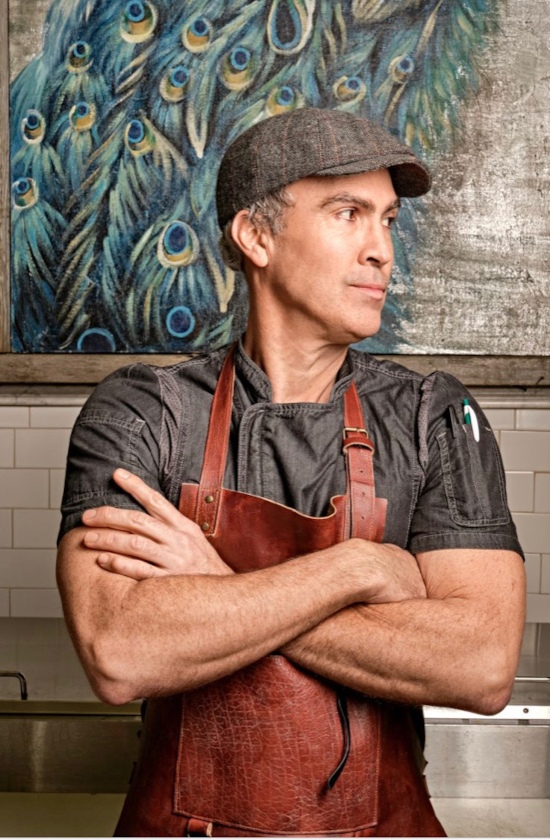

Owner & Chef

At 20, I was making 1,000 canapes a day at the St. Francis [hotel] in San Francisco,” Muszynski recounts, citing priceless apprenticeship experience, as well as French formal culinary school graduation in New York City and a hospitality management degree from Mercyhurst University in Pennsylvania.

From there, it was on to big-time gigs at Def Jam Recordings as a corporate chef and catering privately to cognoscenti — both noteworthy and notorious — whose names we’ve all heard bandied about over years of network news cycles.

From food-eccentric super-celebrities to the highest-profile politicos and their purported cronies, Muszynski’s cozied up to them in their kitchens and traveled the world as they made moves that made history. Regaling me with such stories (some highly redacted, I suspect), Muszynski also mentions that he had his own chocolate factories in Hawaii and New York.

C. King & Co. History

On New Year's Day, 1838, George King founded, The King store on the site where the Schaible Garage recently stood on East Michigan Avenue. Charles and Edward King, sons of George King, took over the business from their father, and were partners under the firm name of G. & E. King. Edward later withdrew, and Charles King and his son, Charles E. King, were partners under the name of King & Son. Charles King passed away in 1883; John G. Lamb entered the business in 1887, and the firm name was changed to Charles King & Co. In 1840 the store was moved to a frame building at 101 West Michigan Avenue, where it remained until 1858, when the present building was erected.

www.annarbor.com: Before Ypsilanti's first supermarket

History

History of 101 W.Michigan Ave.

By Laura Bien

The founding of the King grocery store in 1838 followed the settling of Ypsilanti by only fifteen years. At the time there were about 120 houses in the village. Many log structures remained but among them were ambitious edifices of stone, brick, or frame construction.

The food problem was often a pressing one and much reliance was of necessity placed upon wild game. At first all groceries were brought from Detroit. The road was almost impassable to an ox team and it sometimes took three days to make the thirty-mile trip. For years after its opening, the Detroit road ran through seas of mud and over miles of jolting corduroy [log roads]; no teamster thought of leaving home without an axe and log chain to cut poles to pry his wagon out of the mud.For a time the road was so impassable that travelers had to come from Detroit by way of Plymouth and Dixboro. For visiting and trading, settlers gladly endured a twenty- or thirty-mile ride over bottomless roads. As early as 1829, settlers in the St. Joseph valley journeyed 150 miles to Ypsilanti to get a few rolls of wool carded at Mark Norris’ mill, to buy a little tea and dry-goods, or replenish the whiskey barrel. The transportation of heavy freight was dependent on the Huron River; flat-bottom boats were poled up the river to the Rawsonville landing, some getting through as far as Ypsilanti.

The King store was founded by George King on New Year’s Day, 1838, on the site where the Schaible Garage recently stood on East Michigan Avenue. Mr. King and his two sons had come to this country from England in the latter years of his life. For a year previous to the founding of the store, George King operated the Stack House, a hotel founded by a Mr. Stackhouse several years earlier. I have often wished that I had a picture of this original store and knew how they conducted their business under all the existing handicaps. In 1840 the store was moved to a frame building at 101 West Michigan Avenue, where it remained until 1858, when the present building was erected. During the construction of the new building business was conducted around the corner on South Huron Street, where the Barker Electric Shop now stands.

Charles and Edward King, sons of George King, took over the business from their father, and were partners under the firm name of G. & E. King. Edward later withdrew, and Charles King and his son, Charles E. King, were partners under the name of King & Son. Charles King passed away in 1883; John G. Lamb entered the business in 1887, and the firm name was changed to Charles King & Co. Charles E. King and John G. Lamb operated under this firm name until the death of Charles E. King in 1913; the same year Charles King Lamb entered the business and the firm name was then changed to John G. Lamb & Son. John lamb was in the store for fifty-three years, until his death in July, 1926.

In the early days it was the custom for farmers to bring their produce to the store to trade. Due bills were then issued for the cash transactions and the buyers, in turn, used them as negotiable paper in making other purchases in the village. At the end of the year the merchants met to settle up their accounts; in fact, merchants’ accounts with each other were balanced only once a year. Charles King & Co. was the first store to start cash transactions; that is, they closed each deal instead of allowing credits and debits to continue for a period of time.

Nearly everything was sold in bulk and there were no canned fruits or vegetables. Coffee was sold in the green berry and later roasted in the home. The main staples at this time were flour, which was often sold by the barrel, sugar, tea, coffee, soap, and potatoes; also a complete line of bulk seeds, lime, and cement, the latter being purchased by the car load. Common barrel salt was also purchased by the car load and was the only kind used at that time. The original account book of the store, dating back to 1838, shows a wide range of commodities: among these are hay, spring wheat, buckwheat, cigars, venison (indicating that deer meat was not uncommon), also poultry, pork, whitefish, beer, and whiskey. The King store always aged their own cheese. They would purchase about one hundred cheese, which came packed in thirty-pound molds, open them periodically, grease them on top and bottom and then turn them. This process was continued for from four to six months, until the cheese was ready to sell. Cider was purchased in barrels and held until it turned into vinegar; the third floor of the store was used for the storage of these barrels of cider vinegar. Dairy butter was another item of which a very large volume was sold. The buying of butter was a great problem, because no farmer’s wife wanted to be told that hers was not up to par. In fact the store, in its efforts to be tactful, sometimes purchased butter when they knew it would have to be sold to the packers for a few cents a pound. To be a good butter-tester was quite an art and a store-keeper prided himself on his ability to distinguish good butter. The process used to keep dairy butter sweet was to place a layer of cheese-cloth on top, then cover with a layer of salt, about a half inch, then another layer of cheese-cloth. A paper was then tied tightly over the top and the crocks placed in barrels and placed in the basement. This process would keep it sweet for several months.

Even more recently, the store handled wash-boards, lamps, wicks, chimneys and burners. The only laundry soap available was yellow soap in bars, and sal-soda was the only water-softener; blueing came only in quart bottles, not the concentrated type of today. Black peppercame in 150-pound barrels, and the old-fashioned cracker-barrel containing Vale & Crane crackers was a regular store feature. Pickles came in 50-gallon casks and molasses only in 60-gallon barrels to be sold in bulk. Lamb & Son was the only store to continue the sale of molasses in bulk, and people would come from as far as Detroit to get it.

The Civil War period was a very difficult time for the store. As in the wars since then, prices soared very high and price adjustments caused many difficulties. Revenue stamps were used to tax many commodities. I might add that, a good many years afterward during a cleaning-out process, two bushels of invoices on which revenue stamps had been placed were offered for sale at $5 a bushel. A man bought the two bushel for $10, and later realized over $2,000 from their sale.

One of the difficulties of merchandizing in the early days was the lack of containers, boxes, or bags. Cornucopias were used in handling some bulk goods. I can imagine the difficulties encountered in wrapping up twenty pounds of sugar or salt. I have heard that housewives had specially-made sugar containers which they took to the stores to have filled.

King & Co. had its own delivery service which, in the beginning, was very difficult to operate. As there were only 25 telephones in the city, boys went from house to house by bicycle to take orders, which were later delivered. When the delivery-man had finished his trip he would spend the balance of his time working in the store. The Merchants’ delivery was started about 1910, and was a cooperative effort on the part of the merchants to give better service at a lower cost. This was successfully operated until 1933, at which time it had to be taken over by the individual stores. Before the days of automobiles, which enable people to go to the country and do much of their own buying, the volume of store buying was in much larger quantities. During this time, the Dunlap Store joined us in purchasing car-loads of peaches, stone ware, salt and sugar. My father used to go to the store at four o’clock when a car-load of peaches had arrived in order to get them in shape to sell.

At the same time John G. Lamb went into the store, the wages were $3 a week, in contrast to the present wages of from $40 to $50 a week. Up to 1920, store hours were from 5:30 a.m. to 9 p.m. on weekdays and midnight on Saturdays. On holidays, stores were always open until noon. This is quite a contrast to the comparatively short hours of stores now-a-days, seldom open more

than 9 to 6.

The policy of the store was always cleanliness and orderliness but not until after 1920 was any effort necessary for display. The windows were more or less used for holding bulk containers to relieve congestion in the store. From 1920 to 1925 more attention was given to windows and they were used really to display merchandise. In 1925 new fixtures were introduced which were to revolutionize the grocery business: display was the new element: counters in front of the shelves were removed and price tags placed on each item. This enabled the customer to examine the merchandise and know its cost. The Lamb store was remodeled, adopting these new ideas, in 1929. This new era was largely brought about by the chain-stores who were masters in the art of mass display. They forced the service stores to be on their toes every minute: the problem was to buy in large enough quantities to get the best possible prices in order to meet the competition of the chain-stores. The service store prices were unfairly compared to the chain-store prices without sufficient allowance being made for the service rendered. Telephone, delivery service, and charge accounts were costly items of expense. It was quite rare after this time for a store to have 100% of its customer’s business: the housewife woud take advantage of the week-end specials at the chain-store and then have her daily delivery from the service store on possibly very small items. It is an interesting conjecture whether, after these hectic days of wartime buying, the busy housewife and tired war-plant workernow spending hours over her shopping and carrying all of the merchandise herself, will wish to return to the service type of store where she can telephone in her order and, luxury of luxury, have it deposited for her on her own kitchen table. The swing may be again to this type of store.

The John G. Lamb & Son Grocery Store was closed out in July, 1942, completing nearly one hundred and four years of service to four generations or more of Ypsilantians and their rural neighbors. Miss Julia Stevens, who has just passed away at the age of one hundred years, had been a continuous customer of the store for eighty-four of the one hundred and four years of her life.